I went to get my scripts, the cops beat me up and took me to Pankrác

Download image

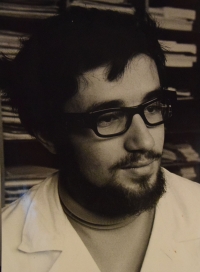

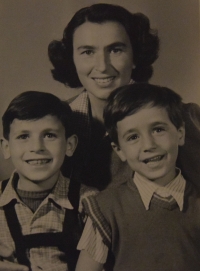

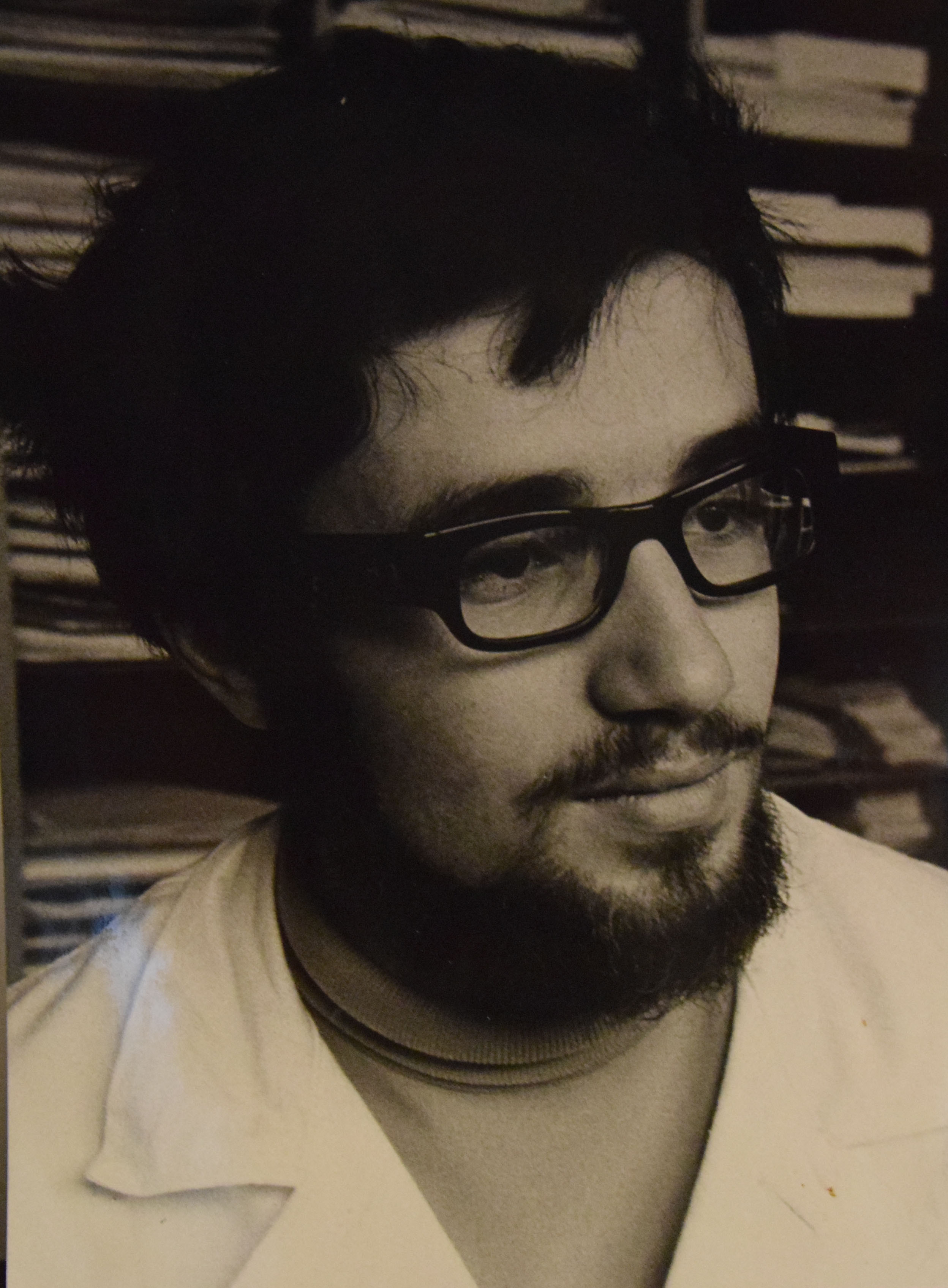

Milan Kodíček was born on February 12, 1948 in Prague to Zdeňka and Arnold Kodíček. Both his parents came from Jewish families. They met in Great Britain, where they went in 1939. His father worked as a military doctor, left England in 1944 and returned to Czechoslovakia with Svoboda’s army. After the war his mother went as a nurse to Terezín, which was then struggling with a typhus epidemic. A large part of both families did not survive the Second World War. His parents left the Jewish community after the war. Milan Kodíček studied chemistry at the Faculty of Science of Charles University in 1966-1971. During protests on the first anniversary of the Soviet occupation in August 1969, he was beaten and arrested on Wenceslas Square. He spent ten days in a cell, although he joined the demonstration by accident. From 1971 he worked at the Institute of Haematology and Blood Transfusion. Since 1985, he was kept by the State Security Service (StB) as a person under investigation (PO) in a file with archive number KR-831086 MV under the code name Brit. During the Velvet Revolution he was the chairman of the Civic Forum at the Institute of Hematology and Blood Transfusion. Since the 1990s, he has been teaching at the University of Chemical Technology (VŠCHT) and has contributed to several textbooks. In 2001 he was appointed professor. In 2024, he served as a member of the board of directors of the Journey Home organization, still teaching at the VŠCHT and living in Prague.