Eva Kočanová, roz. Markovičová

* 1922

-

"When it was -12, -15, -18 degrees Centigrade in the night, and you had to stand at the cannon, you were responsible for another 14 sleeping people in a zemlyanka [earth shelter] plus two cannons. There were always two guards at one unit, each for two cannons. And when you go on your shift you get 200 grams of vodka. It is normal, in that freezing weather it is nothing.

And it happened to me in Vasilkov... I had my duty from eleven to one, and when I started it seemed it was a light drizzle outside. And as I was returning to zemlyanka (there were seven people on one zemlyanka – six, because one was always on guard), so I come in, I woke up Tydyr, Mikhal, he was sleeping next to me. You know, one girl along with six blokes in one zemlyanka, that is... So I say: ‘Come on, get up, take off my shoe!’ I could not do it by myself alone. And he is taking off my shoe and my trousers. –‘I do not want to have my trousers taken off but my shoe!’ –‘Girl, the shoe is frozen down onto the trousers!’ See, to sleep in a zemlyanka on spruce branches under one green blanket, in the clothes you had on during your duty you cannot change into pyjamas. There are no pyjamas as it is a luxury. And washing yourself? This way: you go out, wash yourself with snow, rinse yourself, and that is it. Alhough there was one guy who kept bringing us water, it used to happen that even that water would freeze."

-

"Well one day I... Every morning we had to attend a half-hour drill, it was a terrible thing. The soldiers slept in the barracks, we did in private apartments. They found us accommodation with families. So we said – why should we attend the drill, we can come afterwards. Yes, great, we come after the “half-hour”, eat and go to the training on the cannons. But our boys, the tearaways of ours, fellow fighters, they said: How come our girls do not attend the “half-hour”? Are they not the same soldiers we are?!

Well that is where I met my husband, at this “half-hour”. One day at noon we had our lunch and we sat after finishing it, relaxed, waiting for a line-up march back to the training at the cannons. And there he is, my future husband, coming to our table and says: get up, girls, at my command! We look at him, he is not from our unit actually, what does he want – ‘get up, girls, at my command’? We remain sitting, does he mock us? So we stay in our seats. He went to his commander, as we did not react to him. He was perfect at training. So the commander comes and says: Girls, lance-corporal Kočan will lead your “half-hour”. At 12.30PM! Do you know what that meant? It was horrible. We just soaked in our own sweat! So we practised. We all cursed him. Well, after two, three days, I went to cinema with him and so it started, and lasted for another 37 years."

-

“There was an article saying the Soviet Union was a paradise. The people can study, work. So I wanted to see it for myself. And I crossed the border illegally. Because I lived four kilometres away from the border, I knew when the patrols would change up and down. So instead of going to church we crossed the border. We crossed it along with my friend, well of course we did, and Stalin said the Hungarians sent us as spies. And so that we could not spy on them they locked us up in Siberia. Well first there was Stryi, Skolno, Kharkiv, Lviv, Kharkiv... In Kharkiv, I was sentenced to three years for crossing the border illegally. They transported me to Vorkuta, I was cutting down trees there. They gave me an axe... And I fell ill there, I came into hospital, and there I met a Ukrainian nurse from Mukacevo, [Transcarpathia,] who I asked if she could help me not to return back to that work. So she managed along with the doctor my transfer to the Moldovian Soviet Republic. I went on the train for ten days, approximately. And there it was already nice, they had small houses there, like supermarkets today. So there was a sewing factory. The long military coats were sewn there, and I was sewing collars on them. To earn 700 grams of bread I had to sew on 300 collars."

-

E.K.: “Well, the end of the war... Do you know that one can hardly believe that all the horror is actually over? So it was really an experience, indeed, one of the nicest, to know it is over.” Interviewer: “Did you come to Prague with the army?”

E.K. “No. I did not come to Prague, to be honest. Here, there is a secret, and that is... I became... Well... You know, I became pregnant whilst in the army. When I told my husband about it and that I intended to get rid of it, he said I must not because that equals to killing a baby. So I said: ‘But it is war! What if they kill you?’ He said: ‘If they kill me somebody will take care of you.’ I said: ‘Who would?’ – ‘Well you can go home, or...’ He tried to change my mind. My husband did not go to church but he was religious, believing that one must not kill a baby. So I was in the seventh month of my pregnancy two months before the end of the war when I left my unit. I could use my uniform as usual. Only when I started to imagine seriously what would I do if I lost my arm or leg in an accident I left being a cannon operator - in the seventh month of my pregnancy. And I spent the rest of the war in Lučilna in Slovakia. There were these... You know the Russian girls who were with us... the young ones joined the army and their parents went to a reserve unit. There they repaired clothes – just what was needed. So in Lučilna was such a reserve unit. I was just worried all the time during those two final months of the war so that my husband would not get killed. So when my son was born he weighed only 1,8 kilos.”

-

E.K.: “The first years in the army are shocking. Everybody training, discipline, morale. You know when I see the army nowadays I say – a mess! Compared with the discipline we had. Because as I watched “The good soldier Schweik” and today’s army I thought: exactly the same. How high discipline and morale we had: it did not exist what does today. I just say to myself: where did the then-society bury itself?”

Interviewer: “Could you describe the ‘then’?”

E.K.: “How to describe it... It was strict. First, I worked with the telephonists. So I received two drums of cable and laid them, they connected it and we rang each other. We dragged the drums and there was a Soviet anti-aircraft defence unit.”

Interviewer: “That means it was at the Soviet army.”

E.K.: “No, it was the Soviet Army. It was at Novokhopersk. So we said to ourselves, that is great. To sit on a cannon, rotate it to the left, to the right, upwards, well that is fab, that would be enjoyable. So all of us girls resolved to apply for it. And so we did. They gave us an excursion, we proved competent, and so we were assigned to the anti-aircraft unit.”

-

Full recordings

-

Mladá Bolesav, 05.02.2004

(audio)

duration: 44:22

Full recordings are available only for logged users.

“General Svoboda shook our hands and said: ‘Girls, I am proud of you all.’”

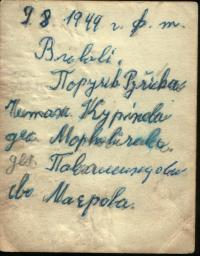

Eva Kočanová, born Markovičová, was born in 1922 in a Ukrainian family in Transcarpathian Ruthenia. After the Hungarian occupation she emigrated to the USSR, where she was arrested and sentenced to three years for crossing the border illegally. She worked in a forest in Vorkuta and in a labour camp in Moldava. After the establishment of the 1st Czechoslovak Field Battalion she was released as a Czechoslovak citizen into the army. She served in the anti-aircraft artillery, made the journey from Buzuluk to Slovakia, and participated in shooting down 9 planes. At the end of the war she became pregnant, and in the seventh month of her pregnancy, she abandoned her fighting unit. After the war, she married the father of her child and along with her husband she stayed in Czechoslovakia. The husband served in the army, they moved house often. She did a number of jobs including being a housewife. She keeps contact with the other veterans until the present day. She holds several decorations.