We had to black the windows out at night. When a dog barked, we were anxious at what was going to happen

Download image

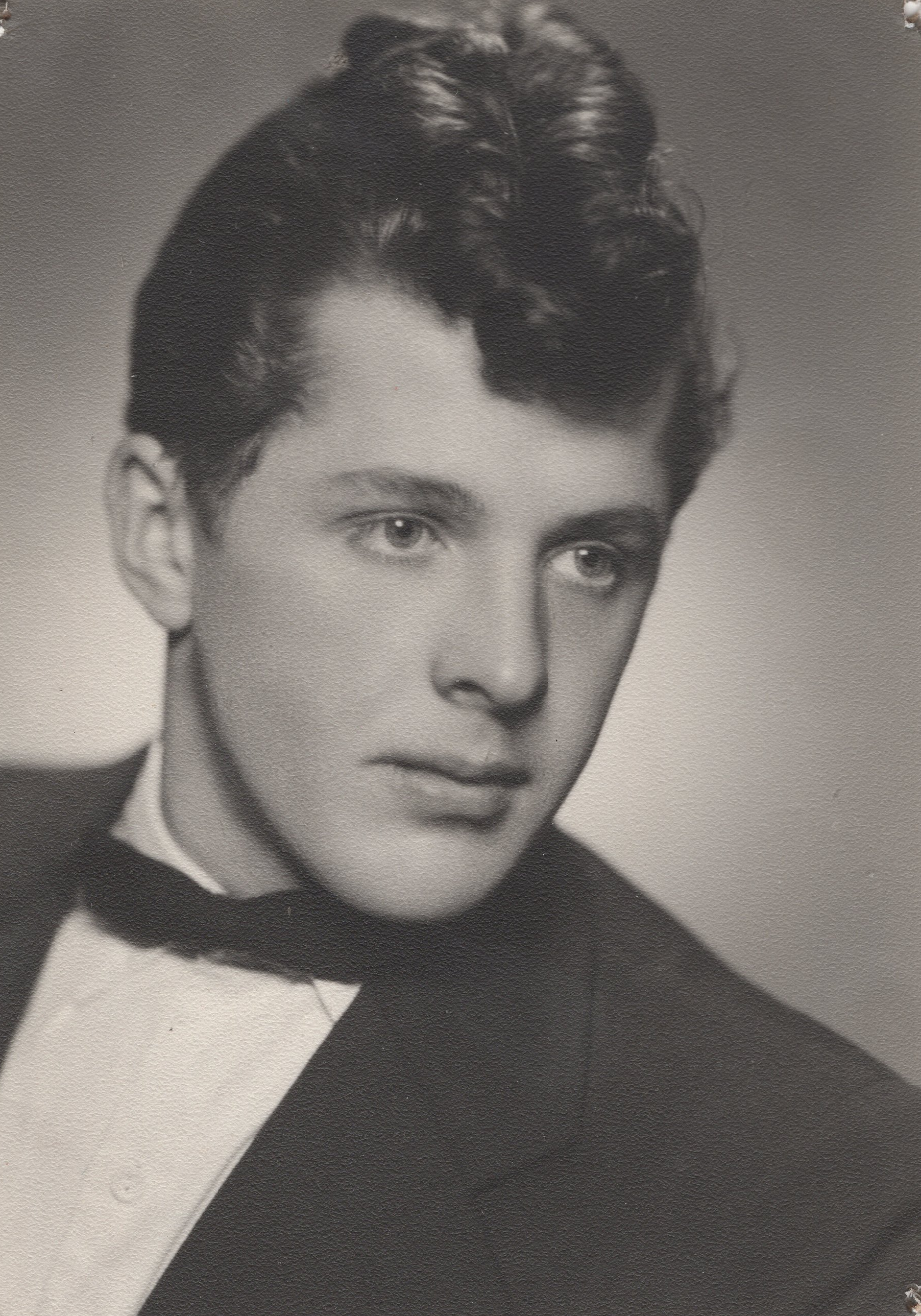

Vladimír Knob was born on 5 March 1939 in Ulbárov, one of the Czech villages in Volhynia where his family had been farming for three generations. He spent the early years of his life in a region where the front line passed through twice. He saw attacks on the Czech minority, looting, clashes between Ukrainians and the Red Army, and the execution of soldiers who tried to rape his relatives. After World War II, he and his parents left the Soviet Volhynia for their old homeland. They arrived in Moravice in the Opava region in April 1947, taking a dilapidated house and deserted fields left by deported Germans. The Knobs brought their Orthodox faith, a strong sense of belonging and hard work, and resistance to collectivisation, which still hit them in Czechoslovakia after February 1948. This was followed by the confiscation of farm machinery, swaps of land for more distant and less profitable plots, predatory pricing for their produce and finally forced entry into the coop. Vladimír Knob left his ancestors’ livelihood and went to study at the high technical school in Ostrava-Vítkovice. He did not get to graduate. Instead of resitting a final exam, he joined the army in 1958. Back in the civilian life, he joined the Vítkovice Ironworks, got married and started a family. He and his wife raised three daughters. He worked in the steel mill until retirement in 1994. Over time, he held various positions within the production process, working his way up to a foreman. After August 1968, he was expelled from the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia for opposing the invasion, but fortunately for him and his relatives, the normalisation regime did not persecute him despite accusations of spurring his colleagues to do the same. Retired, he moved to his wife’s native town of Fulnek where they both lived at the time of filming (2025). He never forgot Volhynia or his compatriots. Vladimír Knob keeps in close touch with them regularly through his association activities.