I behaved in such a way so that they would not approach me with an application to the Czechoslovak Communist Party but so that they would not fire me at the same time

Download image

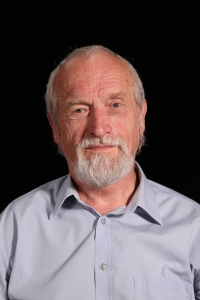

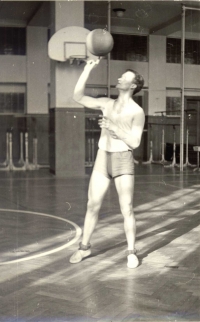

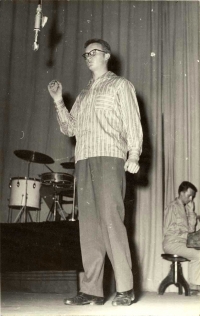

Jiří Klíma was born on 31 December 1942 in Prague to a family of Josef Klíma who was the first leading Czech Orientalist, historian of Cuneiform, of the Ancient Near East, translator from the Sumerian and Akkadian languages. His mother Věra, née Erbenová worked as a Latin and French teacher at grammar school for three years, she later worked in National Medical Library as a professional librarian. Jiří grew up with his older brother Pavel and younger sister Ludmila. The family spent the end of WWII in Horní Bousov where during the last days of the war father Josef Klíma interceded on behalf of the villagers on whom the Nazis wanted to take revenge for an attack on a tank. He taught at the Faculty of Law of Charles University until political cleansing in 1948. The same year, Jiří started to attend first year of Church school in Ječná street. In 1959, he and his schoolmates from the last year of secondary school started the first rock band Sputnici that was highly popular until its dissolution in 1963. He studied at Institute of Physical Education and Sport and the Czech Language from 1959 to 1964 and he got a placement as a teacher in Plasy. He experienced politician liberation and Prague Spring there and he started a local group of Club of Committed Independents (KAN). He returned to Prague in 1968 where he spent a year teaching at a vocational school and then he started to teach at Budějovická Grammar School where he worked until 1986. He was employed at the Pedagogical Research Institute (VÚP) in the last years of the 1980s. In November 1989, they were active during the general strike and participated in the origin of Civic Forum at the Pedagogical Research Institute. He led Civic Forum in Prague - Modřany until the elections in 1990. He joined the Office for the Protection of the Constitution and Democracy (now the Security Information Service, BIS) after the revolution and he worked there for 17 years until his retirement.