You can always say no. Also to the ŠtB agent

Download image

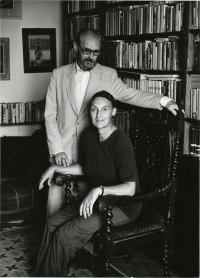

Eva Karvašová was born in October 1932 in Piešťany as the daughter of a local pharmacist Kornel Ruhmann. In the times of the Slovak state, she was expelled from school and reassigned to a single class, apparently because of her evangelical religion. As a child, she helped the partisans, and her father supplied the partisans with medical supplies. He was also imprisoned for it. After the change of regime, she was not admitted to graduation due to her origin. Her first husband, Herman Klačka, a diplomat close to Vladimir Clementis, was sent to prison for sedition by the Communists. Her second husband, playwright Peter Karvaš, was first interned in a concentration camp. He later served on the KSS Central Committee and, after disagreeing with the entry of the Warsaw Pact troops, persecuted as an enemy person. ŠtB tried to dissuade her from her relationship, this ended in her departure from Slovak Radio. They also offered her cooperation, which she refused. She and her husband lived in seclusion and under police surveillance. She lives in Bratislava. For example, she is dedicated to the charity International Women’s Club Bratislava, of which she is a co-founder.