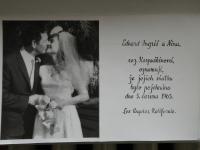

Already as a child, I had thought that if I was to marry someone, he would have to be tall with dark curly hair. And that is the man that Eduard Ingriš was!

Download image

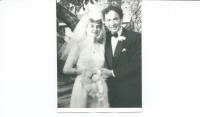

Nina Ingrišová (née Karpuškinová) was born on the 14th of June, 1931, in Brno. Her father, Viktor Vasiljevič Karpuškin, was part of the Russian Cossack emigration of 1921. He studied geodesy at the Technical University in Brno. Her mother, Marie Brychtová, was from Veverská Bítýška. She graduated from a secondary economics school and worked in Brno in the central office of the Czechoslovak People’s Party. In April 1945, the Karpuškins fled the Republic with other Cossack families, heading West away from the approaching Red Army. Their journey into the western occupation zone took them to Munich. They ended up in the Memmingen refugee camp in the autumn of 1945. It was not until 1949 that the family received permission to emigrate to South America. Nina Karpuškinová had gone to basic school in Brno during the War. She completed her secondary education while in Germany at the Memmingen grammar school. Later while in Brazil, she applied herself to operatic singing, appearing on the Ipanema Opera stage. From 1951 to 1952 she worked as an interpreter and guide for Aerovias do Brazil at the São Paolo Airport. In 1957, the family moved Los Angeles, California, USA. Nina secured for herself a place in the foreign department of the Bank of America. The Karpuškins kept in contact with the Czechoslovak ex-pat community in the US. They took part in the cultural activities of Czechoslovaks in Los Angeles, working with Eduard Ingriš among others. Ingriš arrived to the US from Peru in 1962. Nina Karpuškinová took part in the staging of Ingriš’s operettas in Tam na horách (There on the Mountains, 1963), Maryša (1964) and Okolo rybníka (Around the Pond, 1965). In that time, the two grew close, and in June 1965 they married. Together they had a son, Eduard, in 1966. In 1968, they started journeying across North America, earning a living through the screening Ingriš’s travelogues from his ventures into Polynesia and the jungles of the Amazon during the 1950s. When after ten hard years of traveling, they decided to settle down, they opened a health food store headed by Nina. In the late 1980s, Eduard sr. came down with a bad illness. Nina sold the store to finance the purchase of a computer on which to write down Ingriš’s memoirs, but he died in 1991 with the memoirs unfinished. Nina worked in the dietary supplement store for another 11 years until she returned to the Czech Republic in 2002. Nina Ingrišová lives in Brno and tries to keep strong the memory of her husband. Eduard Ingriš jr. lives with his family in Prague.