“No money can replace what we’ve lost and experienced.”

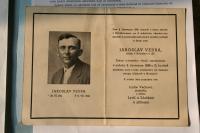

Lýdie Husovská was born on February 4, 1937, in Nosislav. Her father was of a religious and patriotic constitution. Yet before the war, he got to know the Kratochvíl siblings, who were of a similar nature. They emigrated and fought in the western as well as the eastern Czechoslovak army. One of the siblings was landed in Czechoslovakia in 1941 with the mission to contact Lýdie’s father, Mr. Jaroslav Vedra. Unfortunately, the operation was revealed shortly after the landing and Mr. Vedra was arrested. After the Nazis conducted a house search at their place he was taken to Ostrava. Later, he was also interrogated in the Kounic dorms in Brno. Afterwards, he was placed in the Mauthausen concentration camp. In the camp he lived in strenuous conditions and he was also tortured. He died in 1942. The rest of the family survived even though at times they didn’t have even the most basic means. After the war they had trouble with the restitution of their property that had been confiscated during the war. Lýdie’s mother visited Mauthausen in 1946 in order to honor the memory of her deceased husband. She could only come here again in 1973. Lýdie Husovská worked in a savings bank. She keeps coming to the Mauthausen memorial with other witnesses. She lives in her birth-town Nosislav.