If I had been a communist I would have had a better life

Download image

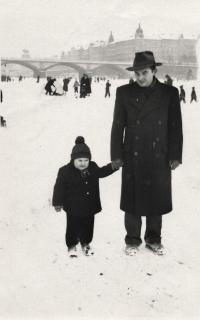

Jiří Hryzlík was born in 1927 in Zábřeh na Moravě into a well-off family. His father was a director of the Central Moravian Power Plants enterprise. Jiří’s business college studies in Přerov were suspended by the outburst of WW II. He was sent to forced labor into a wartime production in the Optika fatory. He witnessed the liberation of Přerov as well as the expulsion of German inhabitants. In 1948 he declined an offer to join the Czechoslovak Communist Party. As a consequence and despite his qualification, he was only able to find blue-collar jobs. He worked as a worker in the Waltrovka factory, later serving in a number of other worker’s professions. In the 1970s he managed to get the job of an enterprise auditor. He had it always written in his papers that he was a politically unreliable person even though he never actually cared about politics.