Without words there is no dialogue and without dialogue there is no democracy

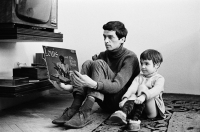

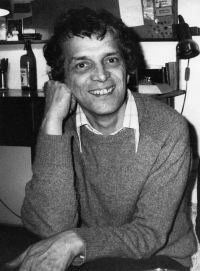

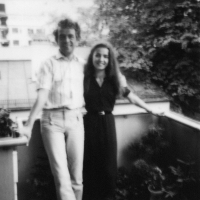

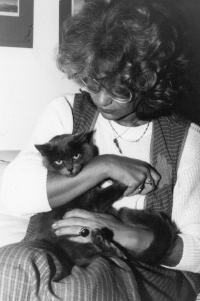

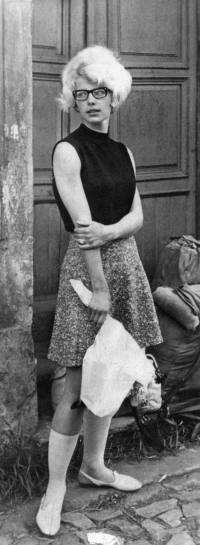

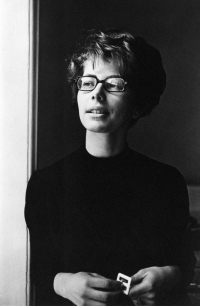

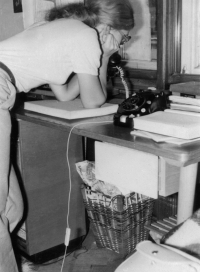

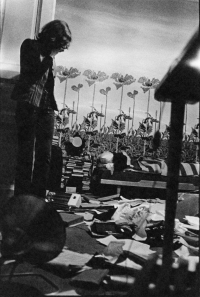

Download image

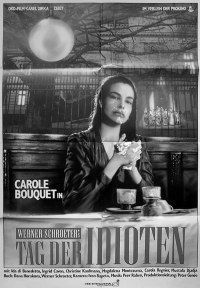

Daňa Horáková was born on 27 March 1947 in Grünbach, Saxony, into a Czech-German family. Her father, Karel Horák, came from a village Catholic background in the Moravian town of Sudice, while her mother, Věra Rebeka, née Rölz, came from a German family of weaving mill owners who had believed in communist ideals for generations. Parents with their daughter moved to Bohemia in 1949, where they lived in a family house in Kunratice near Prague. Daňa Horáková read a lot from childhood and shaped her own intellectual route. After graduating from secondary school in 1965, she was not admitted to journalism faculty because she was not a member of the Czechoslovak Youth Union (ČSM). She worked briefly at the Kovo company and then applied for studies of philosophy and economics at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University. There, from the beginning of her studies, she attended Milan Machovec’s optional seminar Dialogue between Marxists and Christians. In 1968, just after the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact troops, she went to the USA for a one-year internship at the ecumenical seminary Union Theological Seminary in New York. In 1971, in her flat in Pařížská Street, she began organizing debate salons on various academic topics, these were one of the first flat seminars of the normalization period. In 1975, through her friend, film director Pavel Juráček, she met Václav Havel and together they started publishing the samizdat Edition Expedition. Daňa Horáková organized the production of samizdat books entirely on her own, contributing to a total of 88 publications. In the autumn of 1977, she signed the Charter 77 declaration, but before that she had already been the target of pressure from State Security, and had been interrogated and detained many times. Her boyfriend Pavel Juráček, meanwhile, had already left for Germany in the autumn of 1977 under pressure from State Security, but he was able to visit Czechoslovakia. As part of the „Asanace“ Action, State Security also tried to force Daňa Horáková to leave. Eventually, she succumbed to the persuasion of Pavel Juráček, married him in February 1979, and they left together for Munich a month later. As she did not apply for political asylum, she did not have a work permit in Germany and was initially dependent on money earned by cleaning illegally. A poor mental state and the impossibility of creative employment led Pavel Juráček to return to Czechoslovakia in 1983, where he died in 1989. However, Daňa Horáková remained in Germany and gradually put down roots there. She found work as a theatre reviewer for the Bild daily, and her journalistic career continued over the years to the position of head of the cultural section of the German edition of Bild. In the autumn of 1990 she became a German citizen. From 2002 to 2004 she served as Minister of Culture in the Hamburg provincial government. She is the author of several non-fiction books. In 2020, Torst publishing house published her book On Pavel (O Pavlovi), in which she describes her life with Pavel Juráček and her relationship to Czechoslovak dissent.