My father used to say: A decent person can behave according to his/her inner belief even in the worst situations

Download image

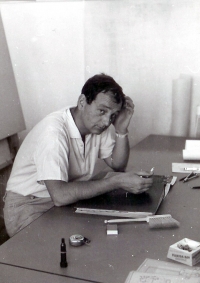

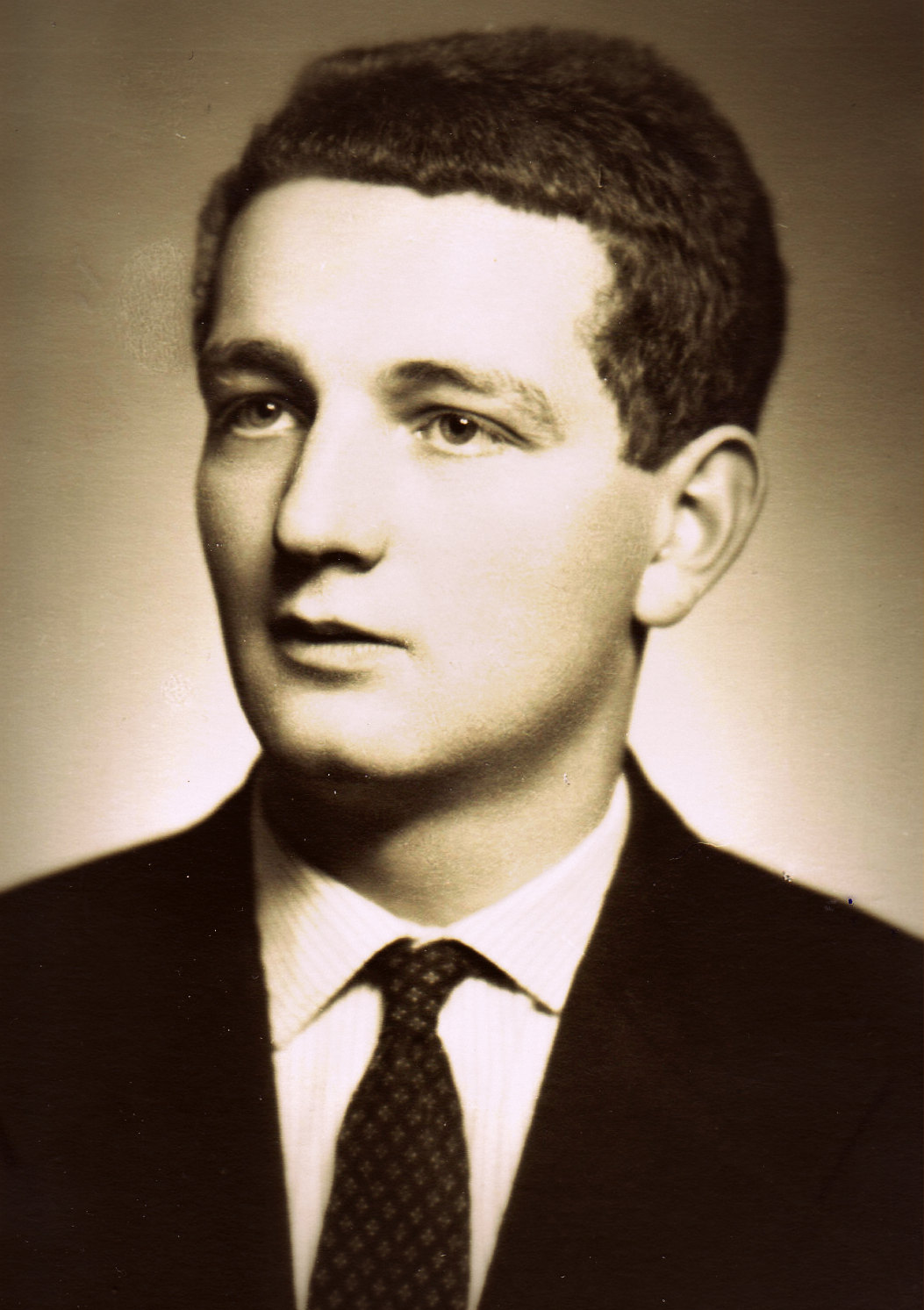

Jan Hlach was born on the 1st of February 1939 in Prague as the first child of three children of a doctor and a lawyer. Shortly after his birth his parents were forced to leave the East Bohemian town of Lanškroun that became part of Sudeten after the Munich Agreement had been signed. They found a new home in South Bohemian Písek. The family suffered Nazi persecution during the war, the husbands of father´s two sisters were executed and also witness Jan Hlach´s father was arrested and imprisoned by Gestapo. Jan Hlach´s parents did not hide their negative approaches towards the communists after the revolution in 1948. Olga Hlachová, witness´s mother, left the law court in Písek in protest. She refused to be part of judiciary that adjusted laws to political aims of ruling party. The same year they were asked to help Dr. František Uhlíř, Deputy of Czech National Social Party, during his flight abroad for which they were arrested and sentenced in 1950. Jan Hlach Senior was sentenced to 14 years and mother to 15 years of imprisonment. Their act was according to the then laws qualified as treason against the people´s democracy state. Their children were committed to father´s sisters´ care. They spent their childhood in material need and disparaging atmosphere that prevailed in tense and stormy times of politically motivated trials. Jan Hlach has traumatizing memories of visiting his mother in prison where the tense meetings were difficult tests both for her and the children. His parents could not return to their professions after release from prison and they worked as blue-collar workers. Their children were also persecuted. Jan Hlach could neither study secondary nor vocational school, after he had finished elementary school. Due to it, he started to work in a factory as a labourer and it was very difficult for him to handle the atmosphere and interpersonal relationships there. The label ‘son of state enemies’ constantly prevented him from any meaningful employment. He spent military service as a driver in Technical auxiliary battalions. He could start studying at university only in the second half of the sixties, at time when the political atmosphere started to get loose step by step. He and his siblings received permission to travel to Austria in summer 1968 where they soon got to know about the Warsaw Pact troops invasion of Czechoslovakia. After their parents came, the whole family decided to emigrate They were granted political asylum in Switzerland. Jan Hlach finished university in Switzerland, then he was a successful entrepreneur and he got married. After he got retired, he started to write books in which he wrote about and also partly dealt with memories of childhood in the communist Czechoslovakia in the fifties. He lived in Switzerland and visited the Czech Republic regularly. He died on February 4, 2025.