“They were transporting us in a cattle train for three weeks in terrible conditions! In prison there were forty of us sleeping in one room. We were even sleeping on the floor. The windows were built-in, there was only a small opening for ventilation up there. For food, they were giving us green tomatoes and a sloppy soup.”

Download image

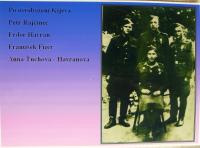

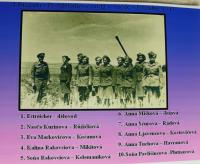

Anna Havranová (born Ťuchová) was born April 7th 1922 in Sinevirská Poljana. Her childhood was affected by an early death of her father Andrej. After the Hungarian occupation of the region in 1939, Anna Havranová decided to escape to Poland, where she wanted to join the forming Czechoslovak legion. She crossed the border at the end of August 1939 with her sister Maria, cousin Vasilina, and another forty young people. The refugees lost their way and wandered in Polish forests for three nights. Then they came across Soviet soldiers who apprehended them. After nearly a year spent in detention in various prisons, on July 2nd 1940 she was sentenced to five years in a labour camp for illegal crossing of the border. The sentence was even harsher compared to a regular three-year sentence, due to the crossing in a large group. After nearly four years spent in Soviet prisons and labour camps, on June 21st 1943 she was finally drafted to the army. After training in Buzuluk she was assigned to anti-aircraft artillery. Following the advice of one doctor, she completed a nursing course and she entered into combat in Kiev and Bílá Cerkev as a nurse. Her remarkable experiences are also captured in the book “From Buzuluk to Prague.” On page 167, readers experience how Anna Ťurchová pulled 42 wounded soldiers out of the combat zone and treated them at Bílá Cerkev. At the beginning of her activity in the army she also met her husband-to-be, Fedor Havran, whom she later married in Krosno. Anna Havranová served as a nurse in all fights of the Dukla operation, she also took part in the liberation on Czechoslovakia. Today, one cannot even count the hundreds of Czech and Soviet soldiers whom she has helped or saved their lives. After the war she settled in Žatec, where she and her husband were running Hotel Praha. In 1947 their son Jiří was born. In a few years, their hotel was nationalized, and the whole family moved to Ústí nad Labem, where her husband found employment as a waiter in Café London. Later, they moved again, to Teplice. Their two daughters, Anna and Marie were born there.