Hitler promised them everything at first – there were drums and horns playing. Then they had to enroll in the army and go to war, where most of them died. The Steinitz family that lived in Olešná had seven boys and not one of them came back home.

Download image

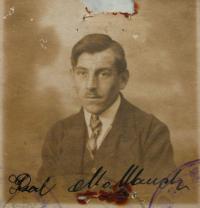

Emilie Hatlová, born Matauchová, was born on May 6, 1925, in Nebužely nearby Mělník in a Czech-German family. Her mother was Czech (born Bělinová), her father Karel Matauch was of German heritage. Emily was their second and last child, she has an older sister Marie Magdalena. She likes to recall her childhood and her grandmother who was expelled from Czechoslovakia in 1945 at the age of 76. Before the war the family used to grow grain, potatoes, turnips and other crops. In Konrádov, in the Kokořín region, where Emily spent a large portion of her youth, Czech and German families lived side by side before the war. Until the end of the thirties, there were no conflicts among them. Emilie went first to elementary school in Konrádov, then to secondary school in Dubé and eventually to a business academy in Jablonec, which however she couldn’t finish because in 1941 she had to work as a forced laborer (because of her partially Czech origin). She worked in a few agricultural operations and then in the arms industry. Her father enrolled in the Wehrmacht and died in 1945 in Polish captivity. After she returned home in 1945 she became a witness of the brutal conduct of Soviet soldiers towards the German population in Konrádov. She had to go into hiding together with the other women in Konrádov in order to escape the Soviet rapists. Due to the fact that she was from a mixed marriage she evaded the deportation of the German population from Konrádov. However, she had to wait till 1945 for the final verdict on this issue. Only then was she free to marry Jaroslav Hatl. She gave birth to two sons - Václav and Jaroslav. She was constantly bullied till the end of the fifties from the authorities and her neighbors, who were denouncing her regularly. Her house in Příbohy witnessed several house searches. In the last few decades, Emilie has been in touch with the expelled Germans from Konrádov and the surrounding area.