Althought there was a war, we had a good time

Download image

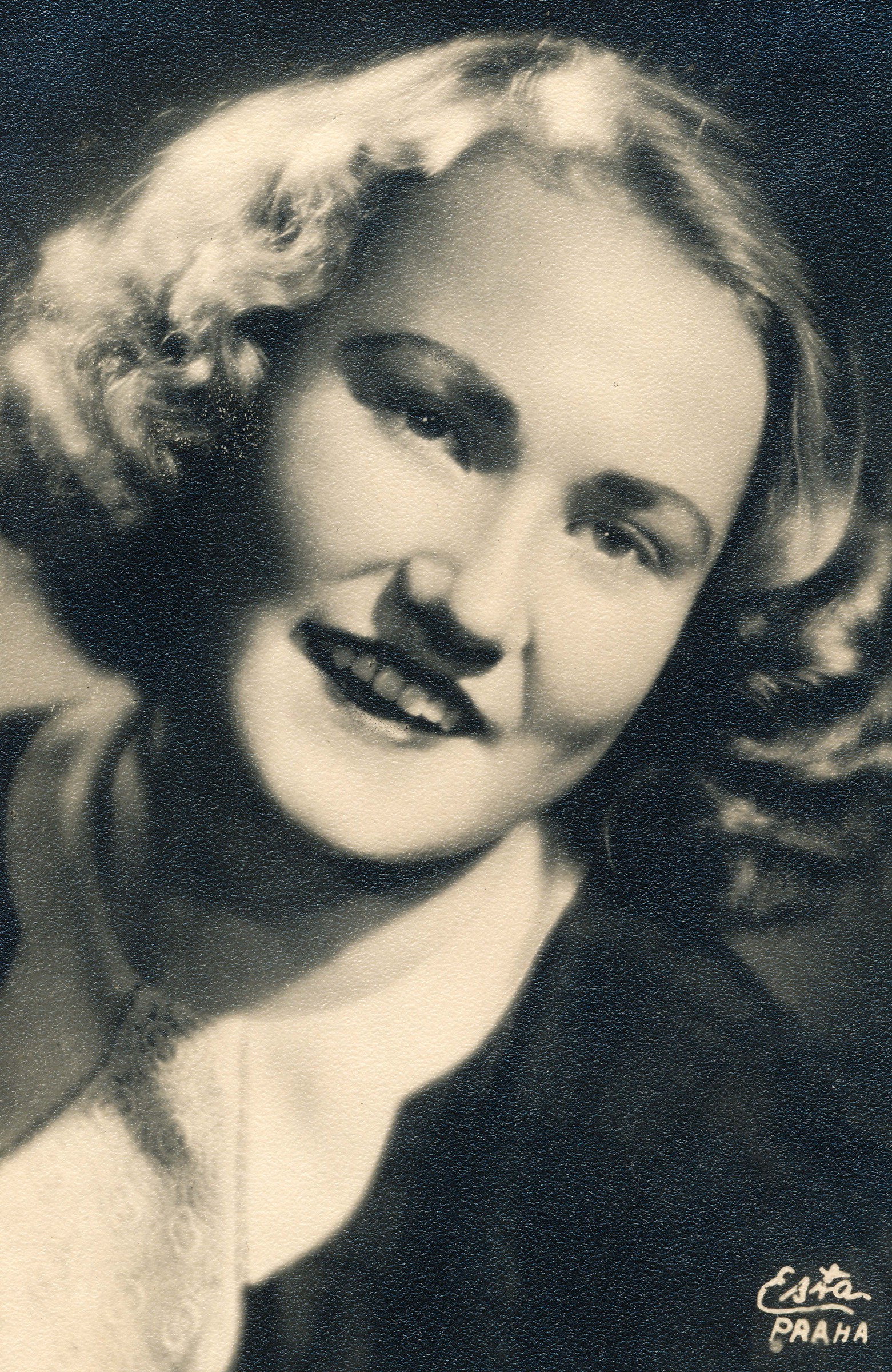

Danuše Hanauerová, née Antoninova, was born on the 8th May 1926 at Kralupy nad Vltavou, where she attended primary and then business high school. She had to stop studying high school in 1943 because of total deployment. She was a witness of American bombing run at Kralupy, German displacement and the terrible ordeal. After the communist revolution, her father deposed from the post of director of local sugar refinery and exiled from Kralupy to Lounovice. Mrs Hanauerova was forced to start working, because her family lacked finances. She found a job in Prague advertising agency, where she worked for 38 years. Due to this work she met her husband. They survived together through all regime changes. Nowadays, Danuše Hanauerová is retired and takes care of her family and family villa.