“I was lost for those brave new tomorrows.”

Download image

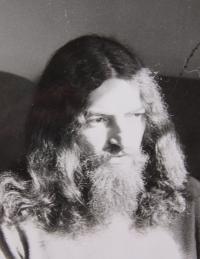

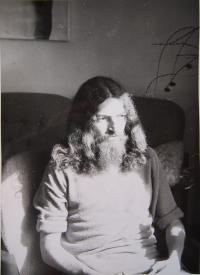

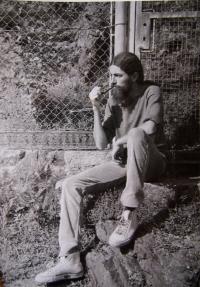

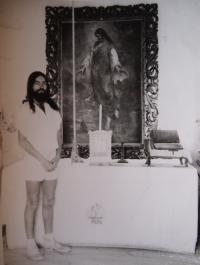

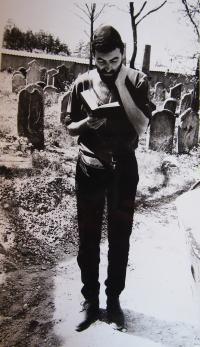

Marcel Hájek was born in 1965 in Pilsen. He was raised by his mother, who worked as a civil servant. He attended Third Grammar School in Pilsen and the Faculty of Medicine of Charles University in Pilsen (FMCU). As a student, he was active in dissident circles in Pilsen, he attended underground-culture concerts, house seminars, and took part in the distribution of samizdat literature, especially the materials of the Jazz Section. In 1988, he and his friend, Vladimír Zindr, wrote a petition to Rudé právo (Red Law, the main Communist Party newspaper - trans.), in which they asked for the publication of the full text of Charter 77. The petition was signed by about seventy-two students of medicine. This was followed by disciplinary action, and the organizers were threatened with expulsion from the faculty. The witness was also questioned by State Security. In November 1989, he headed the FMCU Strike Committee and later the Coordinative Strike Committee. He was active in the Civic Forum. In February 1990, he was co-opted as a deputy of the Czech National Council, but he only held his office until the elections in June 1990. In 1991, he co-founded the Pilsen branch of the Civic Democratic Party (CDP). He was elected as a deputy to the Pilsen city council for the CDP and became a councilor of the city of Pilsen. He held this position until 1998. After completing his studies, he worked at the Institute of Anatomy of FMCU. In 1993-1998, he worked as a surgeon at the University Hospital in Pilsen. He and his family then moved to Botswana, where he was the head doctor for chest and abdominal surgery at Princess Marina Hospital in the capital of Gaborone until 2002. After returning from Africa, he joined the Czech Army, and in 2002-2011, he participated in five foreign missions - two in Iraq, two in Afghanistan, and one in Pakistan. He served as a chief surgeon in NATO field hospitals and head doctor in the field hospitals of the Czech Army. He gained the rank of major. The witness also takes an interest in religious studies, as he is a practicing Jew and a member of the Jewish Community in Pilsen. Besides Judaism, he also studied Islam and Christianity. He graduated in Evangelical theology from the Evangelical Theological Faculty of Charles University in Prague. At the present time, he works for the Emergency Medical Services of Pilsen Region and lectures at the Faculty of Medical Studies of the West Bohemian University in Pilsen. He has published a number of expert medical studies and books.