Even if we face persecution again, we will never change our beliefs.

Download image

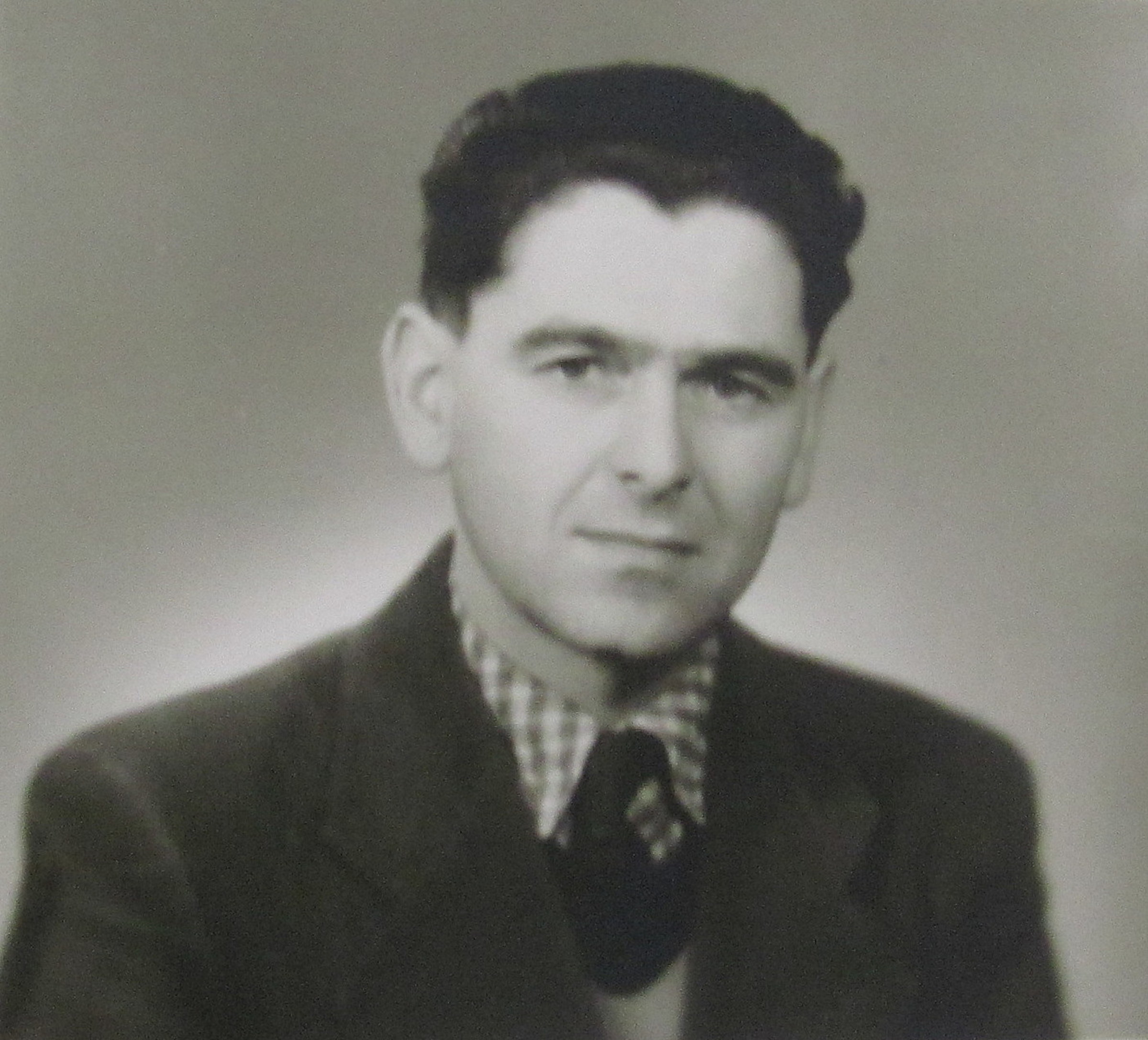

Bořivoj Alois Josef Grepl was born on the 9th of October, 1926 in Hrochov near Prostějov as the tenth child in a tailor’s family. During World War II, three of his brothers were taken to the Reich, while Grepl was able to stay at home. After the war, he left to Brno to study organ playing and obtained a pedagogic education there too. After graduation, he then immediately went to serve his obligatory military service. Just as he was about to go home, the former ministry of defence announced a state of emergency, and Bořivoj Grepl along with three hundred other soldiers had to go dig coal in the Ostrava mines. In 1956, he started acting as an organ player in Břeclav, where he also met his future wife. From the beginning, the family was under growing pressure due to their undisguised religious faith. The witness was promised a job of a pedagogue at a local music school, but this position did not work out. He was then repeatedly fired from many other teaching jobs. Before 1968, Bořivoj Grepl managed to get a proper working contract at a music school. Yet, in the 1970s, he had to face pressure about the religious education of his children and in 1975 he was fired from the music school. According to the school, Grepl’s firing was justified by his succumbing to religion and refusing a scientific perspective of the world. Until the Velvet Revolution, he could only take manual working jobs, but afterward, he was politically rehabilitated. He raised four children together with his wife and now has seventeen grandchildren and twelve great-grandchildren.