If the Mašín brothers had existed during normalisation, I might have joined them

Download image

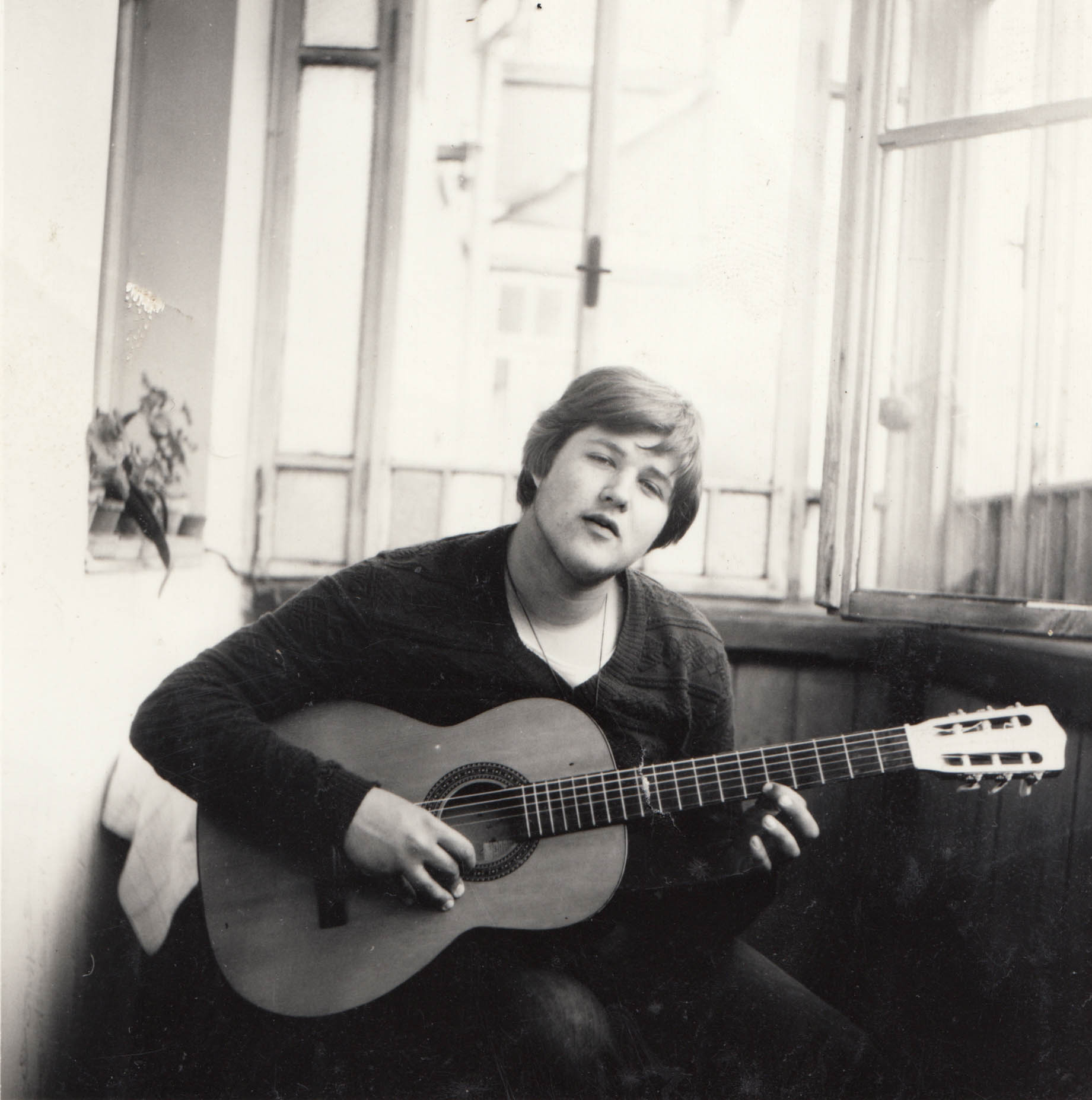

Jiří Fajmon was born on 21 April 1964 in Ústí nad Labem-Trmice. In the 1980s he moved to Liberec and then to nearby Jeřmanice. He was trained at the railway apprenticeship in Nymburk and worked as an engineer for Czech Railways. From an early age, he listened to the Voice of America, Free Europe and the BBC. He distributed anti-regime leaflets and samizdat, secretly smuggled books to Poland and smuggled banned magazines out of Poland. He ministered in church and was baptized at the age of 17. In the 1980s, he was repeatedly interrogated and imprisoned for political reasons - mainly for provocative acts of defiance, such as writing anti-Russian graffiti or defaming the head of state. In 1988, he signed Charter 77 and regularly socialised with Chartists. He became a member of the Movement for Civil Freedom in Liberec and published the samizdat magazine Nákup (Opinions - Culture - Politics). He was the only person sentenced to an unconditional sentence for participating in the so-called Candlemas demonstration in Bratislava on 25 March 1988 and was also prosecuted for disseminating the manifesto Several Sentences. After the fall of the communist regime, he turned to business, running the Eva guesthouse in Kryštofovo Údolí. There he also served as a municipal councillor and devoted himself to charitable activities. In 2016 he received a commemorative decree and a badge of resistance and resistance against communism from the Minister of Defence Martin Stropnický. The project was supported by the Culture and Tourism Fund of the Statutory City of Liberec.