He had had enough of arranging communist shopwindows, so he and the family fled West

Download image

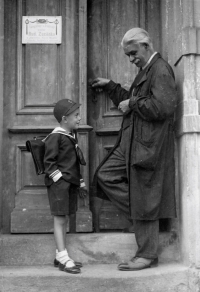

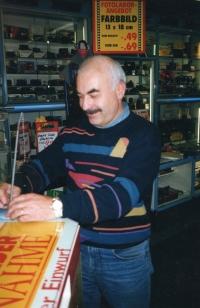

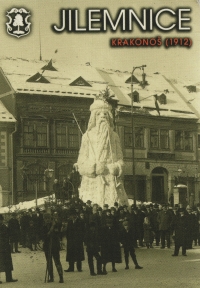

Josef Dufek was born on January 16, 1948, in Jilemnice. His grandfather Rudolf Zuzánek was a Jilemnice-based photographer and sculptor, and Josef inherited his flair for the arts. Unfortunately, he was unable to enter his desired art school because of his parents’ anti-communist sentiments and his father’s refusal to join the Party. Eventually, he trained as a window-dresser in Všešímy. During his military service, he witnessed the Warsaw Pact invasion of Prague in August 1968. He was documenting the clashes between the local inhabitants and the invaders, and himself narrowly escaped getting shot by a Soviet soldier. After his military service, he got a job as a window-dresser at the House of Fashion (Dům módy) in Wenceslas Square. Later, he returned to Jilemnice and started dressing the shop windows of all the Jednota supermarkets in the district. In 1970, he got married and had two children with his wife Ingrid. In 1987, he and his family fled Czechoslovakia via Yugoslavia. The marriage broke down soon after. Josef Dufek started working for the Neckermann department store. He returned to the Czech Republic in the year 2000 and dedicated his time to wood carving. Every year, he would build a snow sculpture of Krakonoš, the spirit of the Giant Mountains, in Jilemnice square. He was still living in Jilemnice in the year 2022 at the time of the interview. His life story was recorded thanks to the support of Liberec Region and SKODA AUTO Endowment Fund.