I told myself : if you survive Osvetim, you will survive everything

Download image

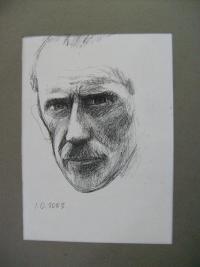

Jana Dubová, formerly Hellerová, was born on August 30, 1926 in Prague. She came from a Czech Jewish family. After the occupation of Czechoslovakia, her father applied for her transport to England, which was organized by Sir Nicholas Winton. She was not accepted, and in April 1942, Jana was transported to Terezín. She stayed in Terezín until 1944 when she was transported to Osvětim. Her mother was executed upon arrival. Jana was chosen to work in a flax factory in the nearby village Merzdorf. The working conditions were harsh, food rations insufficient, and a typhus epidemic raged. Immediately after the camp was liberated by the Red Army, Jana Dubová, along with friends she had made in the camp, followed the frontline on the long journey back to Prague. Of the 30 members of her extended family, Jana and her sister were the only to survive the war. After returning to Prague, she married her boyfriend from Terezín, who had also survived the Holocaust. She studied at the State School of Graphic Arts and worked as a graphic designer. She also painted a series of paintings called “The Dreams of the Dead”, in which she depicted her memories.