“For the rest of his life, almost every night, you could say that every night, he screamed from sleep ... it was part of my childhood ... it wasn’t a human roar, it was like a wounded animal ... every night.”

Download image

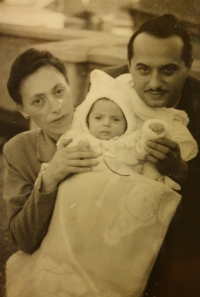

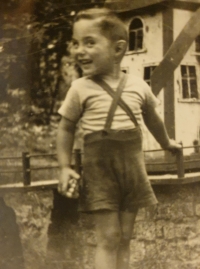

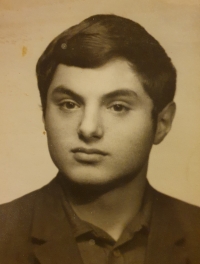

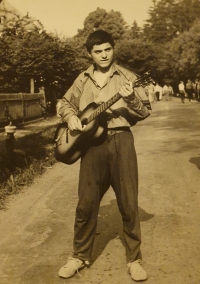

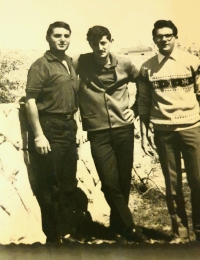

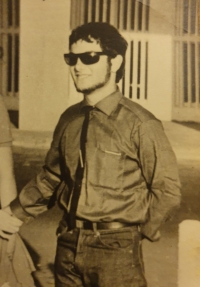

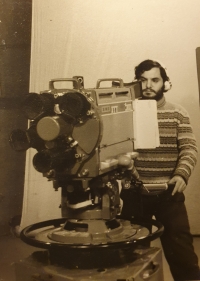

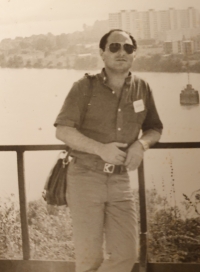

Michal Dor (originally Schnauzer) was born as the third child on July 8, 1948, in a hospital on Šulekova street in Bratislava. He inherited jewish origin from his parents, Blanka and Andrej. The third child, because he was preceded by twins, brothers, who were born during the war, in 1940. Mother Blanka, as single Krajner, came from Topoľčany, from a teaching and even an orthodox jewish family. Father Andrej Schnauzer was of jewish descent, but they did not rank among the orthodox families. Both, together with their families and first-born sons, survived the end of World War II in concentration camps, in Sereď and Terezín. The father’s family survived all, and on the mother’s side, one brother, Laci, died of typhus in Mauthausen. However, World War II was not the only tragedy they survived. They did not avoid the post-war pogrom in Topoľčany, during which father Andrej was attacked by a metal rod and almost did not survive. Subsequently, the whole family moved to Bratislava, where they lived on Klarinská for the first two years and then on Mickiewiczova street for the rest of their lives. They still tried to lead a pious life, according to jewish traditions. As for education, Michal attended primary school on the then Školská Street, which no longer exists. Later, Michal’s parents decided to change and continued at the primary school in Vazovova. In its immediate vicinity there was also a secondary vocational school, which the witness of history chose in 1963, and which it also successfully completed in 1966. The witness of history first visited Israel in 1965 with his mother, and in 1966 he decided to emigrate. He was convicted of treason in his absence and was also labeled a deserter. Life in Israel began by working in a kibbutz, where he learned excellent hebrew. After a year, he was called up for military service, where he took part in several military conflicts. He was even injured. After the war, he completed his technical studies and worked on television. He also devoted himself to the work of a guide, and over time he decided only for this work at a high level. He married for the second time a woman of czech nationality, whom he met during her visit to Israel. They have a fifteen-year-old daughter together. At present, Michal and his family live in the israeli town Givatayim and everyone is happy together.