“I learned to be a photographer and that photo gave me some opportunities to beautify the world, or I don’t want to say a warning, because it’s too big a word, but basically such a small one… to make such a small souvenir of these people… that’s all what I can do. ”

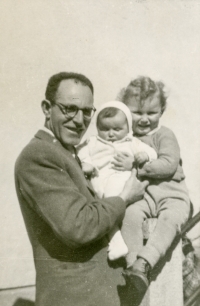

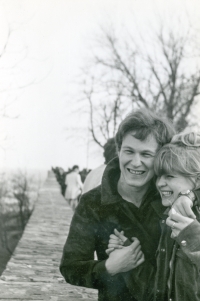

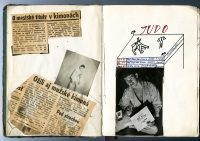

The witness of history Yuri Dojč, a professional photographer, was born on May 12, 1946 in Humenné, into a family of Jewish origin. Both parents worked in the school surrounding, father (originally from Michalovce) as a principal and mother (originally from Nové Mesto nad Váhom) as a teacher. Two years later, a second child, daughter Eva, joined the family. Yuri’s parents became Holocaust survivors. They met at a Jewish school in Michalovce, where they were placed as teachers. As the beginnings of deportations to concentration camps focused on the elderly and young Jewish boys, it was assumed that married couples would avoid hell. There were six teachers at the school, who did not hesitate after this information and formed couples who got married quickly. It was one of these couples that was Yuri’s parents. Since this was not true, they had to flee. With the help of Christian friends, they reached Bánovce nad Bebravou, the village Uhrovské Podhradie. The Králiková family gave them shelter there and they survived. Yuri lived in Humenné for eight years, which is why those early childhood memories come from there, from his birthplace. In the third year of primary school, his family moved to Bratislava. The main reason was anti-semitism and the father’s discomfort as headmaster. The beginnings in Bratislava were not easy, but his father again became the director of a vocational school and so the family got a comfortable apartment. In 1960, Yuri joined the Mechanical Engineering School, which he successfully completed. He was also accepted to the University of Mechanical Engineering, but left it after a year of study. The math was more than challenging and it wasn’t for him. He worked as a draftsman, later a worker at a welding institute. In 1968, he enrolled at Comenius University, Department of Psychology, but did not join there as he emigrated. After a trip and job in England, he decided not to return home, due to the arrival of the Russians in their homeland. He spent a year in London (learning the language) and in 1969 emigrated again, to Canada (Toronto). After two years, he enrolled at university, where he studied photography and accepted a job in a school newspaper. In the same year, he married a Canadian woman who was originally from Hungary. They had a Jewish wedding and in time they had two sons. As a professional photographer, Yuri stood on his own two feet and opened a studio in Toronto. He devoted himself to advertising photographs, which in 1989 were replaced by artistic ones. At present, his home is still in Canada. Unfortunately, his wife suffers from Alzheimer’s, so he faces a difficult life situation. Photography is no longer just his job, but also a hobby or relaxation after many years.