As we approached Haifa, everyone was singing Hatikva and crying.

Download image

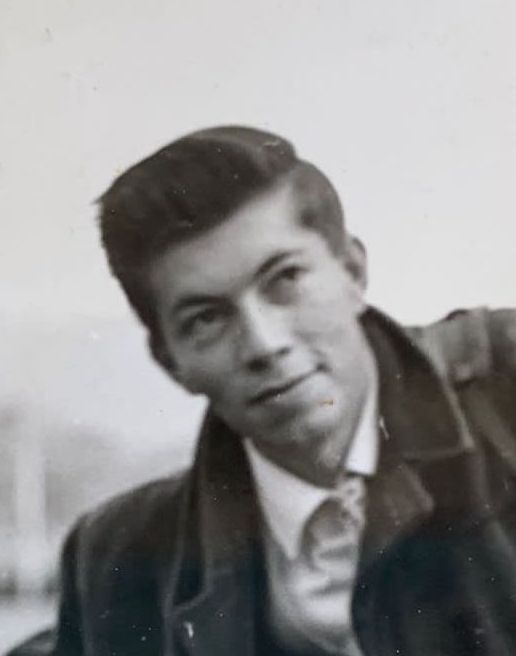

Arie Ervin David was born in Košice in 1936 into a Jewish family. They avoided deportation to concentration camps in 1942 thanks to an exemption for economically important Jews, which was arranged for their siblings by their mother’s brother. In Humenné, they sewed uniforms and boots for the Hinka guardsmen. The parents also had baptismal certificates, which saved the mother, Arie and his sister from deportation after the suppression of the Slovak National Uprising. His father was caught by the Germans and deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, which he survived. After the war, my father successfully ran a business in Košice and saved up to move to Palestine. Arie was active in the Hashomer Hacair movement, and at the age of twelve he went with his group to the newly formed state of Israel in early 1949. Coincidentally, his parents were on the same boat. Arie lived alone in a kibbutz for three years after arriving to Israel, then graduated from high school and became an accountant.From 1959 he studied chemistry and lived in Australia with his mother’s sister. However, he always knew that he would return to Israel. It was after seven years. He was already thirty, he married Miriam, who was born in Prešov, and they had two children. Today, they have five grandchildren and wouldn’t want to live anywhere else but in Israel.