The world will be a good place to live when people respect each other’s rights

Download image

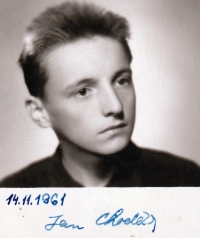

Jan Choděra was born on 24 October 1947 in Jeseník to parents Danica and Jaroslav Choděra. His father served as an evangelical pastor and after the war he was sent to North Moravia to take over the local parish. In the autumn of 1948 he was arrested after being denounced and after a staged trial as the head of a “subversive group” he was sentenced to four years in prison. Shortly afterwards, the family moved back to Prague. Jan graduated from secondary technical school of construction and began his university studies at the Faculty of Construction. He witnessed the intervention of Warsaw Pact troops in August 1968 directly in the streets of Prague, where he was posting anti-Russian leaflets. In March 1969, he was interrogated in connection with the celebration of the hockey team’s victory over the USSR team, and in the same year he was given a suspended sentence for damaging a memorial near Roželov, which wrongfully praised Russian partisans at that place. After this case, he dropped out of his studies and started his basic military service. Subsequently, he was employed at the Prague Construction Renovation and other companies in the construction industry. In 1973 he married Eva Borová. His father-in-law was Josef Bor, a lawyer of Jewish origin who had lost his family in Auschwitz. He wrote his memories of the painful period in the books The Abandoned Doll and The Terezín Requiem. In the 1980s, the witness completed distance studies and graduated from the Faculty of Law of Charles University in Prague. During the events of November 1989 he was in close contact with students as an employee of the Czech Technical University (ČVUT), where he was elected to the first academic senate. After the Velvet Revolution he had managerial jobs in the Diplomatic Corps Services Administration, Česká spořitelna and Agrobanka. In November 1989, he became a member of the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party (ČSSD), in whose ranks he actively worked in important public positions such as a local representative of the Prague 4 Hall, a representative of Prague City Hall, and Deputy Mayor of Prague City.