What I do resembles a picture...

Download image

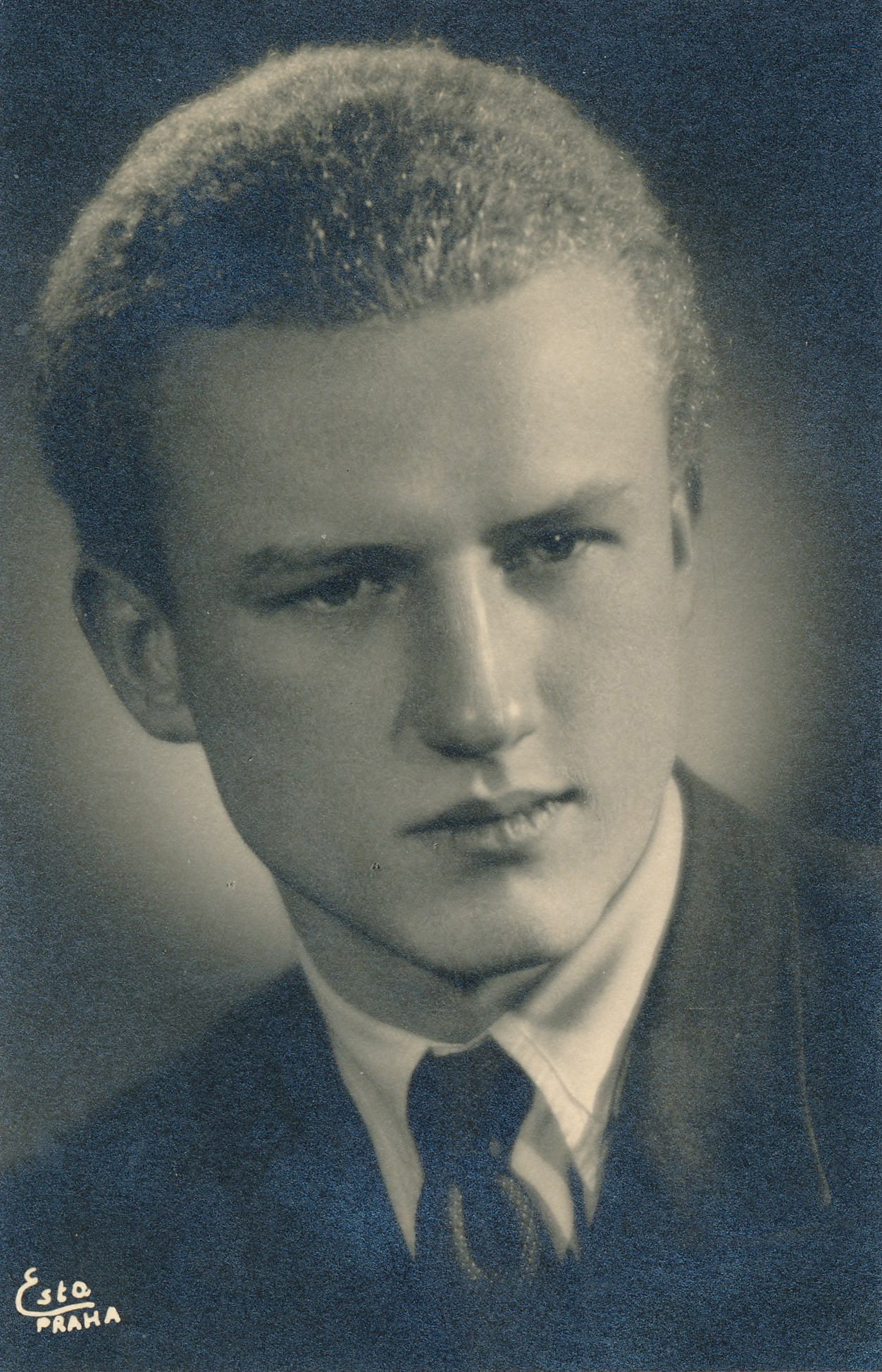

Jiří Chadima was born on 6 June 1923 as the second son of an experienced soldier who, like his wife, came from a tough background. He also spent a large part of his life in uniform, which marked his overall approach to life. Young Jiří Chadima was formed by his father’s strong social awareness and his military vigour. His choice of an artistic career came by chance: when he was at a student’s age, the experimental secondary school Atheneum opened in Prague. It functioned only briefly, from 1936 to 1941, but the school’s art teacher František Sembdner awoke his artistic flair in a major turning point in his life. He went on to study at the State School of Graphics, where he experienced the Prague Uprising. He and several friends joined the Intelligence Brigade, which was one of the successful, leading underground resistance organisations during the war. It was structured and led in a military manner. Its activities included collecting and passing on military intelligence to the foreign resistance. After the war the witness continued his interrupted studies and was accepted to the Academy of Arts, Architecture, and Design in Prague. In 1946 his social awareness was probably what led him to join the Communist Party, where he even functioned as the chairman of one of the Party organisations in the Fine Artists’ Union. All the Party artist associations were active in the reformation movement of the Prague Spring. When these efforts were quashed by the invading Warsaw Pact forces, Czechoslovakia entered a period of normalisation under President Husák, and the regime hunted out “hostile elements” and dealt with them. Jiří Chadima was expelled from both the Party and the Fine Artists’ Fund. Whereas the original Central Union of Czechoslovak Fine Artists, of which he was a member, was dissolved, Chadima was denied membership of the newly established Union of Czechoslovak Fine Artists. He turned to freelance work and succeeded in earning recognition abroad.