You have to leave the house immediately. You’ve been caught!

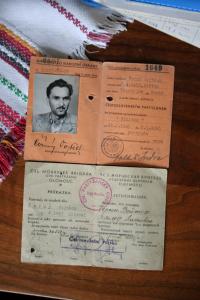

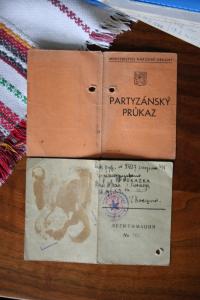

Eva Černá, née Vrbová, was born on 24 December, 1925, in the village of Stražisko in the region of Prostějovsko. Her family lived in a house that was located away from the rest of the village and her dad had a huge garden shop there. Eva had two older brothers, Jaromír and Bohumil. During the war, the whole family was involved in the resistance movement. Jaromír was a slave laborer in the Reich. He later fled and became a partisan in 1944. After February 1948, he became involved in the so-called “third resistance” and was arrested in 1950. He was sentenced to death. Her second brother was a slave laborer in Lutín. He later became a member of the partisan group of Pepa Novák. Eva, her husband and her parents supported the partisans operating in the neighboring area in various ways. After their activities were revealed in the beginning of 1945, Eva’s husband Vojtěch joined the partisans. Eva, her parents and her son, who was just a few months old, had to go into hiding. At first, they were hiding at a family’s household in Moravičany in the Olomouc region and later in a shelter built by the partisans in a nearby forest. Under very primitive conditions, they were able to hold out till the liberation. After the liberation of Czechoslovakia, the whole family reunited again. After the war, she and her husband, who was a teacher by profession, moved to a little village named Křemenec. However, because of their religion, they fell into disfavor. They settled for a longer period in Budětsko, where her husband worked as a director of a local school. Eva worked as a teacher there. In 1968, her husband publicly condemned the Soviet occupation and was fired from the school. Their daughter, Lenka, was dismissed from the university for her activities in the striking committee. Eventually, Eva’s family was transferred to Němčice. They acted in the local theater and befriended the local clerics that had been persecuted.