A pharmacist who saved and risked lives

Download image

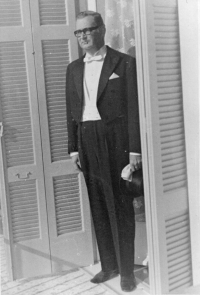

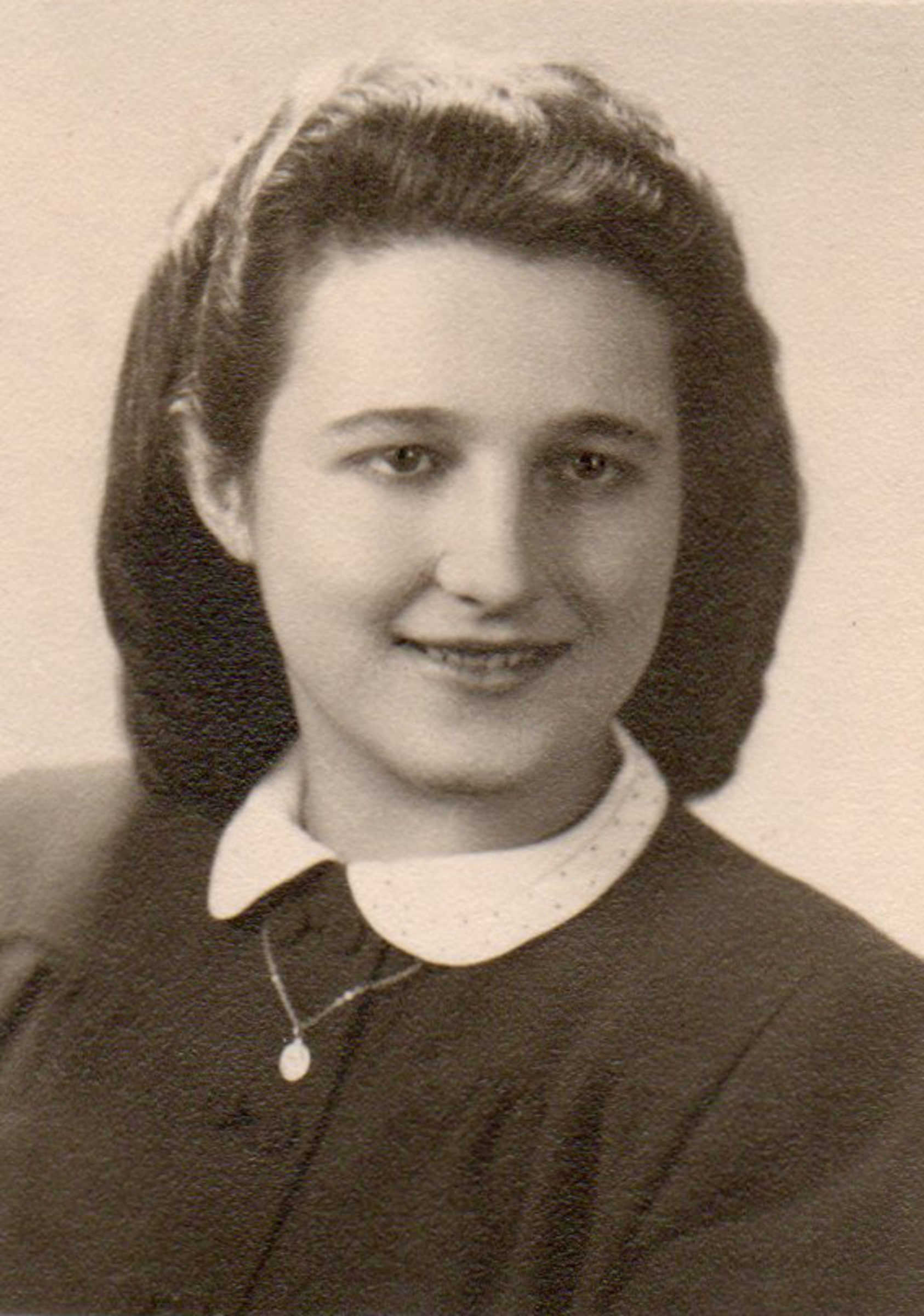

Věra Burešová, née Mušková, was born on 5 February 1924 in Louny. Her father Karel Muška moved the family to eastern Slovakia in 1930 - he worked as a bank manager in Michalovce and then Zvolen. The witness and her sister Hana attended Slovak schools. During the mobilisation in September 1938 and the subsequent establishment of an autonomous Slovak government, her father moved the family to her grandmother’s house in Lochenice near Hradec Králové, where Věra continued her grammar school studies. After her father’s definite return from Slovakia in 1940, the Muškas moved back to Louny. Her mother suffered from fears of anti-Jewish repression the whole war long because she did not inform the authorities of her half-Jewish origin. In May 1943 the witness graduated from the Louny grammar school; her male classmates had been sent off to forced labour in the North Bohemian Coal Mines before they could complete the school. Věra avoided forced labour because she went into training as a pharmacist at the local pharmacy. In 1944 she was asked to prepare first aid kits for partisans wanted by the Gestapo - the resistance group had been deployed near Louny under the command of Vasil Kish. The witness remembers the Louny hero Karel Eisert, who helped the partisans and also supported the families of men arrested or killed by the Gestapo throughout the war. In 1948 Věra Burešová graduated from pharmacy at the Faculty of Natural Sciences. She worked as a pharmacist; in the years 1983-1993 she headed the pharmacy at Vinohrady Hospital. She travelled and stayed abroad twice with her husband, a salesman for Czechoslovak businesses, in Belgium in 1960 and 1961 and in Greece in 1968 and 1969. She raised two children.