I’m looking for the truth about my life

Download image

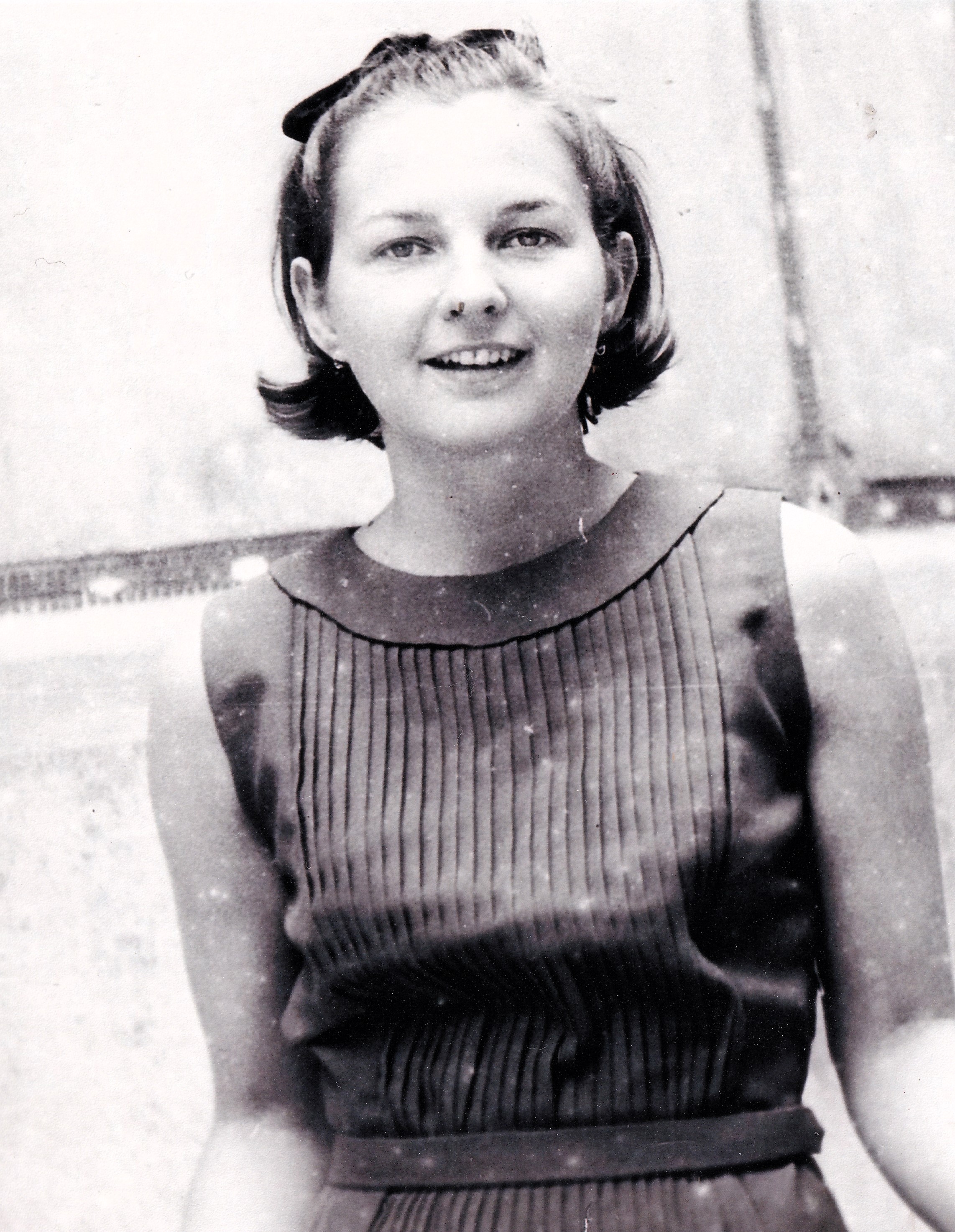

Mária Immaculata Binderová was born in Stupava, Slovakia, on 10 February 1946, the fifth of seven children in the family of the miller Vavrinec and Maria Binder. Her beautiful childhood on the family mill was disrupted by the onset of the communist regime. The mill was nationalised and the father, who was a local authority, was sentenced to ten years in a hard prison after a mock trial. With the mark of a convict’s daughter, the witness trained as a bookbinder. In the mid-1960s she completed a three-year printing course in Leipzig, Germany. After graduating, she worked in a print shop and devoted her free time to working with children without children. She found support in the illegal community of Franciscan Sisters, among whom she was accepted in 1979. Since the raid on the Franciscan order in 1983, she has been under constant surveillance by the State Security. She was greatly encouraged by her participation in the 1985 Velehrad pilgrimage. After the Velvet Revolution she studied spiritual theology in Rome and participated in the revitalization of the Slovak Province of the School Sisters of St. Francis. Since 1998, she has been a member of the contemplative community of the Poor Clares in Brno-Soběšice.