Losing home is terrible.

Download image

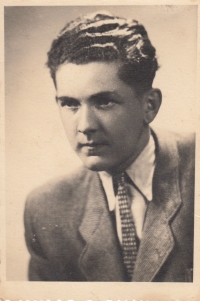

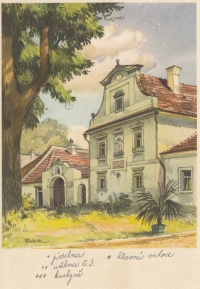

Hana Bicencová, né Lišková, was born on 22 October 1938 in the village of Stříbřec in the Jindřichův Hradec district. She was the youngest of three children. Her parents, Jan and Marie Liška, owned a smaller farmhouse in Stříbřec. The witness graduated from the elementary school in Stříbřec and continued her schooling at the secondary school in Stráž nad Nežárkou. Hana’s brother, Jan Liška, was trained as a cook in Tábor since 1947, where he made friends with his classmate, Alexander Bělohlávek. Bělohlávek fled abroad in 1951. In the summer 1952 he illegally crossed the border back to Czechoslovakia and spent the night at Liška family in Stříbřec. Hana had no idea of his stay abroad, so she was surprised when the state police arrived on 6 October 1952 and arrested her parents. At that time her brother Jan was also arrested. A social worker came for Hana and took her to the children’s shelter home in Vodňany. She suffered hard during her stay. On 16 June 1953, both parents were sentenced to four years’ imprisonment for anti-state activity, unconditionally. Her brother, Jan Liška, left the court with a sentence of fifteen years, including the confiscation of property. Although the witness graduated from elementary school in Vodňany with excellent results, she was sent to the vocational school in Červený Letov, Prague, where she was trained as a toolmaker. Due to loneliness, stress and mental distress in the children’s home and the apprentice school, nerve and epileptic seizures have occurred at the witness. After her apprenticeship she worked in the department of technical drawings in Červený Letov. In March 1955, the mother of the witness was conditionally released for good behavior. Together they returned to Stříbřec. They lived in their home, which then belonged to the Local National Committee (MNV) and they had to pay rent. Her mother worked in a single agricultural cooperative, Hana found a job in a wooden toy factory in Stráž nad Nežárkou. In 1956 the witness married Jaroslav Bicenec. Two daughters were born. His father, Jan Liška, returned from prison for a conditional release in the spring of 1956. In May 1960, the brother Jan also received conditional release. Shortly afterwards, the father Jan Liška committed suicide. In 1964, the Liška family received an order from MNV to move out of their “house” in Stříbřec and then moved to Třeboň, where the witness began to work as a grocery saleswoman since 1965. In 1967, MNV had the house of the witness in Stříbřec demolished. In May 1973 the mother of the witness died. Brother Jaroslav died in 1987. Since 1988, the witness is in full disability pension. After 1989 Hana achieved rehabilitation of her loved ones. She received the land belonging to the family in restitution. Hana managed to get a compensation money for the demolished birth house in Stříbřec after 2000 and amounted to 450,000 crowns. On 20 March 2007 Hana became a widow. In 2019 she lived alone in an apartment in Třeboň.