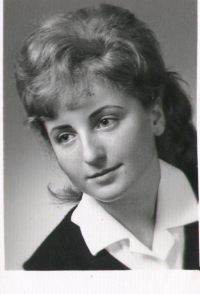

Eržike saved me twice: from deportation and from an orphanage

Marianna Bergida, b. Friedrichová, was born on December 11, 1943 in Košice as the second daughter of a wealthy Jewish family of Friedrichs. After the concentration of Košice Jews in the local brickyard in April 1944, she was brought in a food basket by the educator Eržike and thus saved her from certain death. Her mother and sister Judith died in Auschwitz. After the war, his father, who had been liberated in Mauthausen, returned and became chairman of the Košice Jewish community. During 1949, he helped organize legal evictions to Israel and had to leave with Marianna in the last group. He was arrested in January 1950 and charged with treason and Zionist conspiracy. He refused to sign the confession and was sentenced to three years in prison in a tried trial. A year after his release, he was arrested again and spent one and a half years in the Jáchymov uranium mines. Little Marianna was taken care of by Eržika, thus saving her from the orphanage. Despite the reluctance of the communist regime, after graduating, she managed to graduate from the Pedagogical Institute in 1964 thanks to good people. Her marriage in the Košice synagogue in June 1965 was the first Jewish wedding after the war. After judicial rehabilitation in 1965, his father applied for legal eviction and left for Germany in December. Since then, Marianna has undergone regular interrogations at the State Security Service. At first she took them lightly, but since they did not stop even in 1967, they began to fear with her husband Ivan. With her young son, she visited her father in early 1968 and considered moving out. At that time, in August 1968, Warsaw Pact troops entered the territory of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, and the couple decided to emigrate immediately via Vienna to Germany. They settled near Stuttgart, where their husband Ivan got a job at IBM. Over time, Marianna began working as a teacher. In the 1990s, she worked intensively filming the testimonies of Holocaust survivors for the Spielberg Shoah Foundation. Today she has six grandchildren and she and her husband live in Munich