I was ready to pass or die

Download image

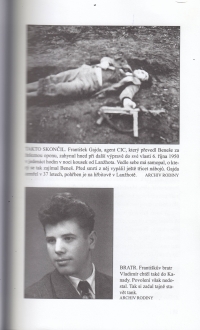

František Beneš was born in the South Moravian town of Hrušky on 11 November 1928 into a family of small farmers. He was trained as a locksmith in nearby Moravská Nová Ves. He witnessed the activities of the resistance during the Second World War in Hrušky, where paratroopers from the Clay (Clay-Eva) parachute unit, commanded by Antonín Bartoš, a post-war member of the National Assembly and later an exiled organiser of couriers and smugglers, were hiding. After 1948, almost fifty citizens of Hruška emigrated, among them František Beneš. A rumour spread through the village that he was also involved in illegal border crossings. Together with the call to the Auxiliary Technical Battalions in Orlová, this was the impetus for his own departure. With a group of ten people, he was taken across the border to Austria on 17 September 1950 by František Gajda, a well-known agent from nearby Lanžhot. After staying in several refugee camps and serving in the French army, he came to Canada, where he lived until 1991. In 1970, his younger brother Vladimír also tried to escape. The escape with his children and wife using a self-constructed tank failed due to a malfunction, and only Vladimir himself made it to America. His family was not able to follow him until 1977. František Beneš returned to Moravia after the revolution. In 2023 he lived with his second wife in Hulín.