The last inhabitants

Download image

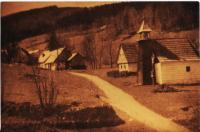

Erika Bednarská, née Schlegelová, was born February 18, 1946 in the now defunct village Hraničky (Gränzdorf in German) in the Rychlebské Mountains (Reichensteiner Gebirge). With its average altitude of 696 m a.s.l., the village was one of the highest inhabited places in the region, and Erika lived there until 1970. Her parents were German nationals, but unlike other people from the village they were not included in the deportation of Germans from Czechoslovakia. Together with four other families they were instead assigned to do work in local forests. However, these four families had to relocate inland in 1948 following an order for the dispersal of the remaining Germans. The only reason why the Schlegel family remained was that they had several small children who would not be able to do hard agricultural work. The other four families later applied for a subsequent emigration to Germany and their request was granted. The family of Franz Schlegel thus remained in Czechoslovakia as the only inhabitants of Hraničky. Nevertheless, they had to leave Hraničky already in 1948. The authorities ordered that the village was to be settled by Greek immigrants who were fleeing the civil war in their homeland. The Schlegel family thus had to move to a dilapidated house which was assigned to them in the village Vojtovice six kilometers away. As soon as they reconstructed the house, they had to move again, and this relocation was followed by another reconstruction of a devastated house. This happened again in May 1949, before the family was able to return to their farm in Hraničky in autumn of the same year. The family members then lived there alone for several years, without electricity and far away from the other villages. They witnessed the demolition of the remaining houses in 1959 and 1960 by soldiers of the Czechoslovak army. Erika left Hraničky in September 1970 and she followed her husband to Žulová. In 2017 she continued living in this village. A month later, her parents moved away from Hraničky as well. The only remaining testimony of the past life in Hraničky is now the viager house of their former farm.