The circumstances forced me, when I defended myself, I thought of nothing

Download image

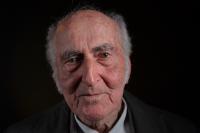

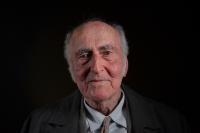

Jiří Bartoš was born on 23 January 1926 in Belgrade. His father Karel was originally from Říčany near Prague. After fighting during the World War I at the Italian front, he remained in Belgrade, working in a pottery shop and marrying Julia Meťko from Daruvar. Jiří attended a Czechoslovak school where he had both Czech and Serbian teachers, and later trained to become a tile layer. Following Luftwaffe’s shelling of Belgrade and the ensuing occupation of the city by the German army in April 1941, he contributed to the family budget by repairing stoves and cookers. Hanged men publicly displayed in the main city square symbolized the brutality of the occupants. Belgrade was liberated in October 1944. The city was cleansed of the Germans; the captured soldiers were given no mercy. Right after liberation, Jiří joined the People’s Liberation Army of Yugoslavia. He underwent a short training, later serving in partisan forces in the Srem region. He was lightly wounded during a battle by the village Vrbani. Following a recovery in Belgrade and Valjevo he was on the way back when he received the news of Germany’s capitulation. In Zagreb, he and his company were ordered to rest on the island of Krk. They disobeyed, instead sailing from Krk to Karlobag and taking part in the battles against the Ustaše. Jiří demobilized in March 1946 and in November that year moved to Czechoslovakia. From 7 January 1947 until his retirement, he worked in a pottery factory in Horní Bříza.