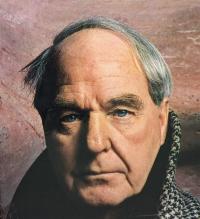

In difficult times I was encouraged by the memory of my parents

Download image

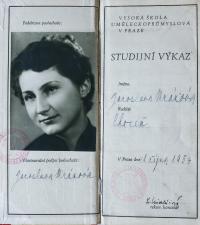

Jaroslava Mrázová was born on 14 March 1935 in Choceň, as the third child of a prominent Czech businessman. Jaroslav Mráz specialised in the production of refrigeration technologies, but he soon expanded into the aviation sector as well. This led to the establishment of a company called Ing. Pavel Beneš and Ing. Jaroslav Mráz, Choceň Aeroplane Factory. By joining forces with the experienced aviation designer Beneš, her father entered the exclusive ranks of the few Czech aeroplane manufacturers, where he gained a prominent position. When the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was declared, the company was forced to switch to military production - again specialising in aviation. Fortunately, the machines it produced were neither fighters nor bombers but instead relatively harmless planes, like the two-seater glider Kranich or the courier plane Storch. It could be said that the factory was much more important to Czechs than to Germans, as it provided a livelihood to many people in the area, and in critical times also a “way out” for people in danger of being assigned to forced labour in the Reich. Although Jaroslav Mráz was branded a “bourgeois exploiter”, his youngest daughter Jaroslava succeeded in graduating from the Academy of Arts, Architecture & Design in Prague. She was awarded the title of ak. arch. (Academic Architect), and she worked in her field of expertise for the whole of her professional career.